John Cabot and Sebastian Cabot. Discovery of North America. John Cabot - he rediscovered North America John Cabot what is named after him

Biography

Origin

Born in Italy. Known by the names: in Italian - Giovanni Caboto, John Cabot - in English, Jean Cabo - in French, Juan Caboto - in Spanish, Joao Cabot - in Portuguese. In non-Italian sources of the late 15th and early 16th centuries there are various versions of his name.

The approximate date of birth of John Cabot is considered to be 1450, although it is possible that he was born a little earlier. Estimated places of birth are Gaeta (Italian province of Latina) and Castiglione Chiavarese, in the province of Genoa.

It is known that in 1476 Cabot became a citizen of Venice, which suggests that the Cabot family moved to Venice in 1461 or earlier (obtaining Venetian citizenship was possible only after living in the city for 15 years).

Trips

Preparation and financing

According to researchers, immediately after arriving in England, Cabot went to Bristol in search of support.

All subsequent Cabot expeditions started from this port, and it was the only English city to conduct exploratory expeditions to the Atlantic. In addition, the letter of honor to Cabot prescribed that all expeditions should be undertaken from Bristol. Although Bristol seems to be the most convenient city for Cabot to seek funding, in the early 2000s. British historian Alvin Ruddock, who adhered to revisionist views when studying the life path of the navigator, announced the discovery of evidence that in fact the latter first went to London, where he enlisted the support of the Italian diaspora. Ruddock suggested that Cabot's patron was the monk of the Order of St. Augustine, Giovanni Antonio de Carbonaris, who was on good terms with King Henry VII and introduced Cabot to him. Ruddock claimed that this was how the enterprising navigator received a loan from an Italian bank in London.

It is difficult to confirm her words, since she ordered the destruction of her notes after her death in 2005. Organized in 2009 by British, Italian, Canadian and Australian researchers at the University of Bristol, The Cabot Project aims to find missing evidence to support Ruddock's claims about early voyages and other poorly understood facts about Cabot's life.

The charter granted to Cabot on 5 March 1496 by Henry VII allowed him and his sons to sail "to all parts, regions and shores of the East, West and North Seas, under British colors and flags, with five vessels of every quality and load, and with any number of sailors and any people they want to take with them...” The king stipulated for himself a fifth of the income from the expedition. The permit deliberately did not indicate a southern direction to avoid conflict with the Spaniards and Portuguese.

Cabot's preparations for the journey took place in Bristol. Bristol merchants provided funds to equip a new western expedition after receiving news of Columbus's discoveries. Perhaps they put Cabot at the head of the expedition, perhaps he volunteered himself. Bristol was the main seaport of Western England and the center of English fishing in the North Atlantic. Beginning in 1480, Bristol merchants sent ships west several times in search of the mythical "Isle of the Blessed" Brazil, supposedly located somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, and the "Seven Cities of Gold", but all the ships returned without making any discoveries. Many, however, believed that Brazil had been reached by the Bristolians earlier, but then information about its whereabouts was allegedly lost. According to a number of scientists, back in the first half of the 15th century, Bristol merchants and, possibly, pirates, repeatedly sailed to Greenland, where at that time there was still a colony of Scandinavian settlers.

First trip

Since Cabot received his charter in March 1496, it is believed that the voyage took place in the summer of that year. Everything that is known about the first voyage is contained in a letter from the Bristol merchant John Day, addressed to Christopher Columbus and written in the winter of 1497/1498. The letter contains information about Cabot's first two voyages, and also mentions the allegedly undoubted case of the discovery of the mythical Brazil by Bristol merchants, who, according to Dey, also later reached the cape of the lands where Cabot intended to go. It mainly talks about the voyage of 1497. The first voyage is covered in just one sentence: "Since Your Lordship is interested in information about the first voyage, here's what happened: he went on one ship, his crew confused him, there were few supplies, and he encountered bad weather, and decided to turn back."

Second trip

The author of the third letter, of a diplomatic nature, is unknown. It was written on August 24, 1497, apparently to the ruler of Milan. Cabot's voyage is only briefly mentioned in this letter, and it is also said that the king intends to supply Cabot with fifteen or twenty ships for a new voyage.

The fourth letter is also addressed to the ruler of Milan and was written by the Milanese ambassador in London, Raimondo de Raimondi de Soncino, on December 18, 1497. The letter appears to be based on personal conversations of its author with Cabot and his Bristol compatriots, who are described as “the key people in this enterprise” and “ excellent sailors." It is also said here that Cabot found a place in the sea “swarming” with fish, and correctly assessed his find, announcing in Bristol that now the British need not go to Iceland for fish.

In addition to the above four letters, Dr. Alwyn Ruddock claimed to have found another one written on August 10, 1497 by London-based banker Giovanni Antonio do Carbonaris. This letter has yet to be found, since it is unknown in which archive Ruddock found it. From her comments it can be assumed that the letter does not contain a detailed description of the voyage. However, the letter may represent a valuable source if, as Ruddock argued, it does indeed contain new information in support of the thesis that the navigators of Bristol discovered land on the other side of the ocean before Cabot.

Known sources do not agree on all the details about Cabot's journey, and therefore cannot be considered completely reliable. However, a generalization of the information presented in them allows us to say that:

Cabot reached Bristol on August 6, 1497. In England they decided that he had discovered the “kingdom of the Great Khan,” as China was called at that time.

Third journey

Returning to England, Cabot immediately went to the royal audience. On August 10, 1497, he was rewarded as a stranger and pauper with 10 pounds sterling, which was equivalent to two years' earnings of an ordinary artisan. Upon his arrival, Cabot was celebrated as a pioneer. On August 23, 1497, Raimondo de Raimondi de Soncino wrote that Cabot “is called a great admiral, he is dressed in silk, and these Englishmen run after him like crazy.” Such admiration did not last long, as over the next few months the king's attention was captured by the Second Cornish Revolt of 1497 . Having restored his power in the region, the king again turned his attention to Cabot. In December 1497, Cabot was awarded a pension of £20 per year. In February of the following year, Cabot was granted a charter to conduct a second expedition.

The great chronicle of London reports that Cabot sailed from Bristol in early May 1498 with a fleet of five ships. It is claimed that some of the ships were loaded with goods, including luxury goods, suggesting that the expedition hoped to enter into trade ties. A letter from the Spanish commissioner in London, Pedro de Ayala, to Ferdinand and Isabella reports that one of the ships was caught in a storm in July and was forced to stop off the coast of Ireland, while the rest of the ships continued on their way. Very few sources are currently known about this expedition. What is certain is that English ships reached the North American continent in 1498 and passed along its eastern coast far to the southwest. The great geographical achievements of Cabot's second expedition are known not from English, but from Spanish sources. The famous map of Juan de la Cosa (the same Cosa who took part in the first expedition of Columbus and was the captain and owner of its flagship Santa Maria) shows a long coastline far to the north and northeast of Hispaniola and Cuba with rivers and nearby geographical names, as well as with a bay on which it is written: “the sea discovered by the English” and with several English flags.

It is assumed that Cabot's fleet got lost in ocean waters. It is believed that John Cabot died en route, and command of the ships passed to his son Sebastian Cabot. More recently, Dr. Alwyn Ruddock allegedly discovered evidence that Cabot returned with his expedition to England in the spring of 1500, that is, that Cabot returned after a long two-year exploration of the east coast of North America, all the way to Spanish territories in the Caribbean.

Offspring

Cabot's son Sebastian later made, in his words, one voyage - in 1508 - to North America in search of the Northwest Passage.

Sebastian was invited to Spain to serve as chief cartographer. In 1526-1530 he led a large Spanish expedition to the shores of South America. Reached the mouth of the La Plata River. Along the Parana and Paraguay rivers he penetrated deep into the South American continent.

Then the British lured him back. Here Sebastian received the position of chief warden of the maritime department. He was one of the founders of the English navy. He also initiated attempts to reach China by moving east, that is, along the current northern sea route. The expedition he organized under the leadership of Chancellor reached the mouth of the Northern Dvina in the area of present Arkhangelsk. From here Chancellor reached Moscow, where in 1553 he concluded a trade agreement between England and Russia [Richard Chancellor visited Moscow in 1554, under Ivan the Terrible!].

Sources and historiography

Manuscripts and primary sources about John Cabot are few and far between, but known sources have been collected together in many scholarly works. Better general collections of documents about Cabot Sr. and Cabot Jr. are the collection of Biggar (1911) and Williamson. Below is a list of known collections of sources about Cabot in various languages:

- R. Biddle, A memoir of Sebastian Cabot (Philadelphia and London, 1831; London, 1832).

- Henry Harrisse, Jean et Sébastien Cabot (1882).

- Francesco Tarducci, Di Giovanni e Sebastiano Caboto: memorie raccolte e documentate (Venezia, 1892); Eng. trans., H. F. Brownson (Detroit, 1893).

- S. E. Dawson, "The voyages of the Cabots in 1497 and 1498,"

- Henry Harrisse, John Cabot, the discoverer of North America, and Sebastian Cabot his son (London, 1896).

- G. E. Weare, Cabot's discovery of North America (London, 1897).

- C. R. Beazley, John and Sebastian Cabot (London, 1898).

- G. P. Winship, Cabot bibliography, with an introductory essay on the careers of the Cabots based on an independent examination of the sources of information (London, 1900).

- H. P. Biggar, The voyages of the Cabots and of the Corte-Reals to North America and Greenland, 1497-1503 (Paris, 1903); Precursors (1911).

- Williamson, Voyages of the Cabots (1929). Ganong, "Crucial maps, i."

- G. E. Nunn, The mappemonde of Juan de La Cosa: a critical investigation of its date (Jenkintown, 1934).

- Roberto Almagià, Gli italiani, primi esploratori dell’ America (Roma, 1937).

- Manuel Ballesteros-Gaibrois, "Juan Caboto en España: nueva luz sobre un problema viejo," Rev. de Indias, IV (1943), 607-27.

- R. Gallo, "Intorno a Giovanni Caboto," Atti Accad. Lincei, Scienze Morali, Rendiconti, ser. VIII, III (1948), 209-20.

- Roberto Almagià, "Alcune considerazioni sui viaggi di Giovanni Caboto," Atti Accad. Lincei, Scienze Morali, Rendiconti, ser. VIII, III (1948), 291-303.

- ·Mapas españoles de América, ed. J. F. Guillén y Tato et al. (Madrid, 1951).

- Manuel Ballesteros-Gaibrois, "La clave de los descubrimientos de Juan Caboto," Studi Colombiani, II (1952).

- Luigi Cardi, Gaeta patria di Giovanni Caboto (Roma, 1956).

- Arthur Davies, “The ‘English’ coasts on the map of Juan de la Cosa,” Imago Mundi, XIII (1956), 26-29.

- Roberto Almagià, "Sulle navigazioni di Giovanni Caboto," Riv. geogr. ital., LXVII (1960), 1-12.

- Arthur Davies, "The last voyage of John Cabot," Nature, CLXXVI (1955), 996-99.

- D. B. Quinn, “The argument for the English discovery of America between 1480 and 1494,” Geog. J., CXXVII (1961), 277-85. Williamson, Cabot voyages (1962).

Literature on the topic:

- Magidovich I. P., Magidovich V. I. Essays on the history of geographical discoveries. T.2. Great geographical discoveries (end of the 15th - mid-17th centuries) - M., Education, 1983.

- Henning R. Unknown lands. In 4 volumes - M., Foreign Literature Publishing House, 1961.

- Evan T. Jones, Alwyn Ruddock: John Cabot and the Discovery of America, Historical Research Vol 81, Issue 212 (2008), pp. 224–254.

- Evan T. Jones, Henry VII and the Bristol expeditions to North America: the Condon documents, Historical Research, 27 Aug 2009.

- Francesco Guidi-Bruscoli, "John Cabot and his Italian Financiers", Historical Research(Published online, April 2012).

- J.A. Williamson, The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery Under Henry VII (Hakluyt Society, Second Series, No. 120, CUP, 1962).

- R. A. Skelton, "CABOT (Caboto), JOHN (Giovanni)", Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online (1966).

- H.P. Biggar (ed.), The Precursors of Jacques Cartier, 1497-1534: a collection of documents relating to the early history of the dominion of Canada (Ottawa, 1911).

- O. Hartig, "John and Sebastian Cabot", The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908).

- Peter Firstbrook, "The Voyage of the MATTHEW: Jhon Cabot and the Discovery of North America", McClelland & Steward Inc. The Canadian Publishers (1997).

Notes

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Dictionnaire biographique du Canada / G. W. Brown - University of Toronto Press, Presses de l "Université Laval, 1959.

- (PDF) (Press release) (in Italian). (TECHNICAL DOCUMENTARY "CABOTO": I and Catalan origins have been proven to be without foundation."CABOT". Canadian Biography. 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2008. "SCHEDA TECNICA DOCUMENTARIO "CABOTO": I CABOTO E IL NUOVO MONDO" (undefined) (unavailable link). Retrieved December 25, 2014. Archived July 22, 2011.

- Department of Historical Studies, University of Bristol. Retrieved 20 February 2011. (undefined) .

Giovanni Caboto was born in Italy. The approximate date of his birth is 1450. In 1476 Caboto became a citizen of Venice. Almost nothing is known about his Venetian period of life. It was probably while living in Venice that Caboto became a sailor and merchant.

Europeans at that period of history were preoccupied with finding a sea route to India, the land of spices, and Caboto was no exception. He asked Arab merchants where they got their spices from. From their vague answers, Caboto concluded that the spices would be “born” in some countries located far to the northeast of the “Indies.” And since Cabot considered the Earth to be a sphere, he made the logical conclusion that the northeast, far away for the Indians, was the northwest close to the Italians. His plan was simple - to shorten the path by starting from the northern latitudes, where the longitudes are much closer to each other. Caboto tried to interest the Spanish monarchs and the Portuguese king with his project of reaching the spice country, but failed.

Giovanni Caboto moved to England and settled in Bristol around mid-1495. Bristol was then the main seaport of Western England and the center of English fishing in the North Atlantic. There the Italian began to be called John Cabot in the English manner. In this country he found support for his ideas, including financial support.

On March 5, 1496, Cabot received a charter from Henry VII, which allowed him and his sons to sail "to all parts, regions and shores of the East, West and North seas, under British banners and flags, with five vessels of every quality and load, and with any number of sailors and any people they want to take with them...” The king stipulated for himself a fifth of the income from the expedition.

Cabot's preparations for the journey took place in Bristol. Bristol merchants contributed funds to equip the expedition after receiving news of Columbus's discoveries. But they equipped only one small ship, the Matthew, with a crew of 18 people. On May 20, 1497, Cabot sailed west from Bristol.

2 Newfoundland

John Cabot stayed just north of 52°N the entire time. w. The voyage took place in calm weather, although frequent fogs and numerous icebergs made movement very difficult. Around June 22, a stormy wind blew in, but fortunately, it soon subsided. On the morning of June 24, Cabot reached some land, which he named Terra Prima Vista (in Italian - “the first land seen”). This was the northern tip of the island. Newfoundland. He landed in one of the nearest harbors (Cape Bonavista) and declared the country the possession of the English king. Then Cabot moved southeast near the heavily indented coast, rounded the Avalon Peninsula and, in Placentia Bay, reaching approximately 46 ° 30 "N and 55 ° W, he turned back to the "point of departure." At sea off Avalon Peninsula, he saw huge schools of herring and cod.This is how the Great Newfoundland Bank was discovered, a large - more than 300 thousand km² - sandbank in the Atlantic, one of the richest fishing areas in the world.

The entire reconnaissance route off the Newfoundland coast took about 1 month. Cabot considered the land he examined to be inhabited, although he did not notice people there. On July 20, he headed for England, keeping to the same 52° N. sh., and on August 6 arrived in Bristol. Cabot correctly assessed his “fish” find, announcing in Bristol that the British now need not go to Iceland for fish.

3 England

After Cabot’s return, a certain Venetian merchant wrote to his homeland: “Cabot is showered with honors, called a great admiral, he is dressed in silk, and the English are running after him like crazy.” This message appears to have greatly exaggerated Cabot's success. It is known that he, probably as a foreigner and a poor man, received a reward of 10 pounds sterling from the English king and, in addition, he was given an annual pension of 20 pounds. The map of Cabot's first voyage has not survived. The Spanish ambassador in London reported to his sovereigns that he had seen this map, examined it and concluded that “the distance traveled did not exceed four hundred leagues” - 2400 km. The Venetian merchant, who reported the success of his fellow countryman, determined the distance he had traveled at 4,200 km and suggested that Cabot walked along the coast of the “kingdom of the Great Khan” for 1,800 km. However, the phrase from the king's message - "to him [who] discovered a new island" - makes it quite clear that Cabot considered part of the newly discovered land to be an island. Henry VII calls it the “Rediscovered Island” (Newfoundland).

4 North America

At the beginning of May 1498, a second expedition under the command of John Cabot, who had at his disposal a flotilla of five ships, set out to the west from Bristol. Even less information has survived to this day about the second expedition than about the first. What is certain is that English ships reached the North American continent in 1498 and passed along its eastern coast far to the southwest. Sailors sometimes landed on the shore and met people dressed in animal skins who had neither gold nor pearls. These were North American Indians. Due to a lack of supplies, the expedition was forced to turn back and return to England in the same 1498. Historians suggest that John Cabot died en route, and command of the ships passed to his son Sebastian Cabot.

In the eyes of the British, the second expedition did not justify itself. It cost a lot of money and did not even bring hopes of profit (the sailors did not pay attention to the country’s fur riches). For several decades, the British made no new serious attempts to sail to East Asia via the western route.

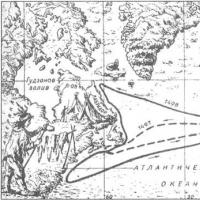

The great geographical achievements of Cabot's second expedition are known not from English, but from Spanish sources. Juan La Cosa's map shows, far to the north and northeast of Hispaniola and Cuba, a long coastline with rivers and a number of place names, with a bay on which is written: "the sea discovered by the English." It is also known that Alonso Ojeda at the end of July 1500, when concluding an agreement with the crown for the expedition of 1501-1502. pledged to continue the discoveries of the mainland “right up to the lands visited by English ships.” Finally, Pietro Martyr reported that the British “reached the Gibraltar line” (36° N), that is, they advanced somewhat south of the Chesapeake Bay.

John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) (born May 23, 1450 - died 1499) - Italian explorer and merchant in the English service, became known in history as the discoverer of the east coast of North America. Route: from Bristol, England to North America; Objective: find a western route to India and China (north of Columbus’s route); Significance: discovery of a significant portion of the coast of North America and the Great Newfoundland Bank.

Origin. early years

Giovanni Caboto, a native of Genoa, was born into the family of a spice merchant. The Cabotos were wealthy merchants, well known not only in their native Genoa, but also in Constantinople itself.

When Constantinople fell under the onslaught of the Turkish hordes and became Istanbul, the family of the future navigator moved to rich Venice in 1461, and he later accepted Venetian citizenship in 1476. From a young age, he made sea voyages and visited Mecca, the holy city of the Arabs. At the same time, the idea came to him about the possibility of reaching India from the West. But he did not have enough money to organize the expedition.

Expeditions

Travel to Asia

Giovanni entered the service of a Venetian trading company. On the ships that were provided by her, Caboto went to the Middle East for Indian goods. When visiting Mecca, communicate with Arab merchants and spice traders. Cabot asked them where the merchants delivered their goods from. From what he heard, he was able to get the idea that the strange spices came from lands located somewhere far from India, in the north-eastern side of it.

The navigator was a supporter of the progressive and still unproven at that time idea of the spherical shape of our planet. He understood that what is the distant northeast for India is the relatively close northwest for Italy. The thought of approaching the treasured lands, going west, did not leave him.

Preparing for the expedition

1494 - Giovanni Caboto moved to live in England where he accepted British citizenship. In Britain, his name began to sound like John Cabot. He settled in the westernmost port of the country - Bristol. At that time, the idea of reaching new lands by another, Western route, was literally in the air. The first successes made by Christopher Columbus (the discovery of new lands in the western part of the Atlantic Ocean) prompted Bristol merchants to equip an expedition.

They were able to obtain written permission from, who gave the go-ahead for research expeditions with the aim of annexing new lands to England. The merchants equipped one ship with their own money, which was supposed to go on reconnaissance. John Cabot, at that time already an experienced and eminent navigator, was entrusted with leading the expedition. The ship was named "Matthew".

First expedition (1497). Discovery of Newfoundland

1497 - John Cabot's first expedition took place and was successful. On May 20, the traveler sailed from Bristol to the west and all the time stayed just north of 52° north latitude. On June 24, he reached the northern tip of the island, later named Newfoundland. The navigator went ashore in one of the ports and declared the island the possession of the British Crown. Moving away from the island, the ship went along its coast, to the southeast. Soon the traveler discovered a vast shelf, very rich in fish (later this area was called the Great Newfoundland Bank and for a long time was considered one of the largest fishing areas in the world). With the news of his discovery, John Cabot returned to Bristol.

Second expedition (1498)

Bristol merchants were inspired by the results of the first expedition. They did not hesitate, and equipped a second, this time more impressive expedition - it already included 5 ships. The expedition was undertaken in 1498, and John's eldest son, Sebastian, took part in it. The discovery of North America did take place this time. Although the information that has reached us is very scarce, it is known that the expedition managed to reach the mainland.

During the trip, the eastern and western coasts of Greenland were explored, and they visited Baffin Island, Labrador and Newfoundland. Having walked along the coast south to 38° north latitude, they did not find any traces of eastern civilizations. Due to a lack of supplies, it was decided to return to England, where the ships arrived in the same 1498.

This time the expectations were not met. Only 4 ships returned from the expedition; the flotilla was led by Sebastian Cabot. The fifth ship, on which John himself was, disappeared under unclear circumstances.

At that time, few people could be surprised by such incidents. The ship could get caught in a storm and be wrecked, it could get holed and sink, the crew could be hit by some fatal disease contracted during the journey. Many dangers await sailors who are left alone with the formidable elements. Which of them caused the famous traveler John Cabot to disappear without a trace remains a mystery.

The British, however, as well as the sponsors of the expedition, decided that the expedition was unsuccessful because a lot of money was spent on it, and as a result the travelers did not bring anything valuable. The British expected to find a direct sea route to “Catay” or “India,” but they received only new, practically uninhabited lands. Because of this, in the coming decades the British did not make new attempts to find a shortcut to East Asia.

The son of the famous traveler, Sebastian Cabot, continued his father's work. They left a bright mark on the history of the era of great geographical discoveries. He undertook expeditions under both the British and Spanish flags, exploring North and South America.

The names of the discoverers of South America are surrounded by worldwide fame. Christopher Columbus, Fernando Cortez, Amerigo Vespucci... Rivers, countries and even the continent itself were named in their honor. How many people know the fate of the English navigator John Cabot, one of the first travelers to that part of the world where the richest and most powerful states are now located, and the discoverer of the eastern part of Canada.

John (Giovanni) Caboto was born in Genoa in 1450. When he was 11 years old, the Caboto family moved to Venice, where Giovanni subsequently served in a trading company. This change was not accidental: after the conquest of Constantinople, many merchants and sailors emigrated to Europe in search of work. From a young age, Kaboto had to sail a lot in search of overseas goods - the Middle East, Mecca, European countries. He had a dream - to find the land of spices. Step by step he approached his goal, asking other merchants for the way to the cherished land. In 1494, Giovanni moved to England, and began to be called John Cabot - in the English manner.

In those distant times, enlightened people believed in the round shape of the Earth, and the navigator John Cabot was no exception. Heading west, he hoped to land on the coveted islands from the east - this was still an unattainable, but already quite tangible idea. Columbus's discovery inspired the enterprising merchants of Bristol and pushed them to a bold expedition designed to discover the unknown lands of the north, and then get to the spice islands, India and China. England could afford this daring trick because it did not obey the Pope, nor did it participate in the redistribution of the world with Spain and Portugal. Having secured the support of Henry VII, the Bristol adventurers equipped a ship at their own expense (there simply wasn’t enough money for more ships) and sent it to the west. This fateful ship, with 18 crew members, was named "Matthew" and was captained by John Cabot.

On May 20, 1497, the Matthew sailed from Bristol harbor. That same year, meeting the dawn on June 24, he landed on the northern coast of Newfoundland, where today Canada is located. Stepping ashore, John Cabot claimed the land as English possession, christening it Terranova, and then continued his search towards the southeast. During this search, noticing huge schools of cod and herring, John discovered the notorious “Newfoundland Bank” - a giant sandbank with indestructible stocks of fish, one of the most profitable fishing areas in the world. On July 20, 1497, after a month at the new lands, Cabot ordered the sails to be turned back to England, and on August 6 he arrived safely in Bristol.

The uncharted land discovered by Cabot seemed inhospitable and harsh. There was no gold. There were no spices. There were practically no natives either. There was plenty of fish alone, so there was no longer any need to swim to Iceland for it. But the savvy merchants from Bristol did not despair, judging that it was too early to draw conclusions. New lands have been discovered, which means a second expedition is needed. This time, instead of one ship, as many as five ships went to sea under the command of the same Genoese Cabot. One of his three sons, Sebastian Cabot, was also part of the expedition.

The second expedition began its journey in May 1498. There are two versions of the development of those ancient events. According to one of them, John Cabot died on the road, while the other says that his ship disappeared without a trace along with its captain. But be that as it may, command passed to Sebastian. There is little information left in history about this journey. It is only known that English ships reached the lands of North America in 1498, passing along the entire east coast in the direction of the southwest - all the way to Florida. They returned to England that same year. John's son Sebastian Cabot left his mark on the history of world exploration, exploring both American continents in the service of the Spanish and English crowns.

The Cabots' work was continued by other researchers - English and French, so that very soon the outlines of North America took their rightful place on the geographical map of the world. The blank spot that haunted the minds of thousands of sailors was no longer there. Information about the Cabots' travels is captured in Spanish sources- the flagship of one of the ships of the legendary Columbus expedition, Juan La Cosa, put a new coastline with a bay, rivers and some geographical names on his famous map. It depicts English flags.

Historically significant expeditions did not enrich or glorify (during their lifetime) John and Sebastian Cabot. But thanks to them, England gained the right to dominate the North American lands. She used this right to the fullest, receiving huge incomes from fishing, fur trade and other wealth. In the end, the English colonies formed a new state - the United States of America, where the influence of Great Britain is quite noticeable to this day.

John Cabot's expeditions

When the discoveries made by Columbus became known in Europe, many companies, as well as individuals with sufficient funds, began to equip ships that were supposed to set off for the fabulous riches supposedly hidden in uncharted lands. So, in 1497, English merchants from the city of Bristol prepared one small ship, the Matthew, with a crew of 18 people and invited a certain captain John Cabot, a native of Genoa, as the leader of the expedition.

North America

On May 20, 1497, Cabot sailed west from Bristol and stayed just north of 52° N the entire time. w. The voyage took place in calm weather, but frequent fogs and numerous icebergs made movement difficult. On the morning of June 24, the ship "Matthew" approached some land, later named Terra Prima Vista, which in Italian means "first land seen." This was actually the northern tip of the island of Newfoundland, east of Pistol Bay. In one of the nearest harbors, Cabot went ashore and declared the island the possession of the English king. Next, the British headed southeast, walked along the heavily indented coast, rounded the Avalon Peninsula and saw huge schools of herring and cod. This is how the Great Newfoundland Bank was discovered - a vast shoal in the Atlantic, which is of great value from a fishing point of view.

On the island of Newfoundland, archaeologists have discovered an ancient Norman settlement. This find is irrefutable evidence that long before Columbus and Cabot, the inhabitants of Europe knew about the existence of lands in the West.

Cabot stayed near the coast of Newfoundland for about a month, and then set off for the coast of Europe, still adhering to 52° N. w. Having returned safely to England, Cabot spoke about his discoveries, but for some reason the British decided that he had visited the “kingdom of the Great Khan,” that is, China.

At the beginning of May 1498, a second expedition led by John Cabot, who this time had a flotilla of five ships at his disposal, set out from Bristol to the west. However, Cabot died along the way, and his son, Sebastian Cabot, took over leadership. English ships reached the North American continent and passed along its eastern coast far to the southwest. Sometimes sailors landed on the shore and met people there, “dressed in animal skins, who had neither pearls nor gold” (North American Indians). Due to a lack of supplies, Cabot turned back and returned to England in the same year, 1498.

In the mountains of North America

In the eyes of Sebastian Cabot's compatriots, his expedition did not justify itself. Large sums of money were spent on its organization, and it itself did not even bring hope of profit, since no natural resources could be found in a wild country, in no way similar to India or China. And over the next few decades, the British made no new serious attempts to sail to East Asia via the Western route.

From the book Fraud in Russia author Romanov Sergey AlexandrovichExperiments by John Law Less than a hundred years after tulip mania, a similar epidemic broke out in France, with the same symptoms. Only this was already an acciomania. The Scotsman John Law brought it into society. The son of a goldsmith and moneylender, he was known as a spendthrift, a duelist and

From the book 100 Great Mysteries author From the book 100 great conspiracies and coups author Mussky Igor Anatolievich From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (CL) by the author TSB From the book 100 Great Mysteries of the 20th Century author Nepomnyashchiy Nikolai Nikolaevich From the book The Best Hotels of the World author Zavyalova VictoriaThe German trace of John Lennon Bayerischer Hof, Munich, GermanyIgor Maltsev When the first Beatlemaniacs were little, they didn’t even think about what cities their idols The Beatles visited, and even more so they couldn’t think about what hotels they stayed in. We drew with a pen. V

From the book Petersburg in street names. Origin of names of streets and avenues, rivers and canals, bridges and islands author Erofeev AlexeyJOHN REED STREET On the right bank of the Neva in the Nevsky district, many highways bear the names of people whose activities are in one way or another connected with revolutionary events in Russia and Europe. John Reed Street is named after the American journalist who became famous, the main

From the book USA: History of the Country author McInerney Daniel From the book All the masterpieces of world literature in brief. Plots and characters. Foreign literature of the 17th-18th centuries author Novikov V IThe History of John Bull Novel (1712) Lord Strutt, a wealthy aristocrat whose family has long owned enormous wealth, is persuaded by the parish priest and a cunning solicitor to bequeath his entire estate to his cousin, Philip Babun. To severe disappointment

From the book The Second Book of General Delusions by Lloyd JohnRevisited by John Lloyd and John Mitninson When we created the first Book of Common Errors in 2006, with the help of the tireless and brave work elves of QI, we proceeded from the erroneous premise that our work would deplete the deposits of the Mountain of Ignorance forever, depleting its resources

From the book I Explore the World. Great Journeys author Markin Vyacheslav AlekseevichJohn Ross's second attempt In 1829-33, John Ross appeared again in the North of America. He is already 52 years old, but he is full of desire to still go to the Pacific Ocean. With his nephew James, he organizes an expedition on the steam wheeled ship Victoria. This was the very first steamship

From the book Scams of the Century author Nikolaev Rostislav VsevolodovichUnder the name of John Morgan In July - August 1912, active and extensive preparations for the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, which took place on August 26, 1812, took place in St. Petersburg, and throughout Russia. To this important historical date, St. Petersburg

From the book 100 Great Scams [with illustrations] author Mussky Igor AnatolievichThe Collapse of the John Law System In 1715, the French king Louis XIV died. His heir was only five years old, so the regent, Duke Philippe of Orleans, became the regent. Every step of the regent was watched by his opponent - powerful and much closer in kinship

From the book Self-loading pistols author Kashtanov Vladislav Vladimirovich From the author's bookFake masterpieces by John Myatt The thirst for owning unique works of art has given rise to a “related” business – high-quality fakes. However, only a few forgers manage to create real fake masterpieces that connoisseurs accept as